A partnership with the U.S. Ski & Snowboard became official last May: the Omini brand will kit all sports for the next 10 years.

Release courtesy of Kappa.

Torino, 29 November 2022 – After the announcement on May 10th of a 10-year partnership between Italian brand Kappa® and U.S. Ski & Snowboard, the first winter collection produced by Kappa®’s R&D center is now available online at Kappa.com and inside the main retail stores.

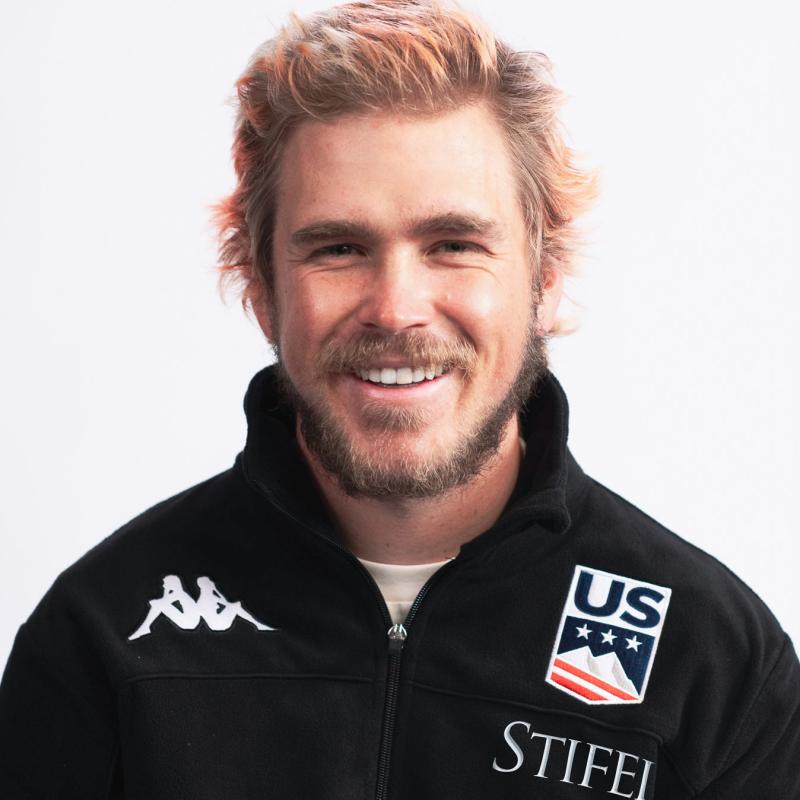

The first Kappa® US SKI & SNOWBOARD offer – activewear version of the racing clothes worn by the athletes on the U.S. team – includes: ski jacket and pants, fleece sweater, ultra-light down jacket, heat-sealed windproof, waterproof down jacket, cotton T-shirt, tracksuit (hoodie + pants), visor hat and a wool hat in dark navy blue with U.S. Ski & Snowboard team logos. There will also be, for a few exclusive items, in white and red, designed to represent colors of the Stars and Stripes.

Six young athletes from U.S. Ski & Snowboard are protagonist of the advertising campaign shot in Salt Lake City (Utah, USA) last October, including alpine skier Bella Wright, freestyle moguls skier Kai Owens, freeskier Jay Riccomini, cross country skier Luke Jager and up-and-coming athletes Izzy Worthington and Bo Giddings.

It is the first time that a single outerwear and racing suit brand appears on the uniforms of all the winter sports teams of the U.S. Ski & Snowboard: alpine ski, snowboard, freestyle, freeski and cross country.

The new Kappa® 4CENTO 400 KOMBAT SL 2022 US uniforms immediately conquered the first two podiums in the FIS Ski World Cup 2022-23 season with a double victory by Mikaela Shiffrin in Levi, Finland, on 19 and 20 November.

ABOUT KAPPA®

Kappa® is one of the brands owned by BasicNet SpA, an Italian company that also owns Robe di Kappa®, Jesus Jeans®, K-Way®, Superga®, Sabelt®, Briko® and Sebago®, leading clothing, footwear and accessories brands for sport and leisure. BasicNet operates worldwide through a network of entrepreneurs who, under license, produce or distribute products with the Group’s trademarks. BasicNet provides these companies with research and development, product industrialization and global marketing services. All business processes take place solely via the internet, which makes BasicNet a “fully web integrated company”. BasicNet, based in Turin, has been listed on the Italian Stock.

ABOUT U.S. SKI & SNOWBOARD

U.S. Ski & Snowboard is the Olympic National Governing Body (NGB) of ski and snowboard sports in the USA, based in Park City, Utah. Tracing its roots directly back to 1905, the organization represents nearly 200 elite skiers and snowboarders in 2022, competing in seven teams; alpine, cross country, freeski, freestyle, snowboard, nordic combined, and ski jumping. In addition to fully funding the elite teams, U.S. Ski & Snowboard also provides leadership and direction for tens of thousands of young skiers and snowboarders across the USA, encouraging and supporting them in achieving excellence. By empowering national teams, clubs, coaches, parents, officials, volunteers, and fans, U.S. Ski & Snowboard is committed to the progression of its sports, athlete success, and the value of team. For more information, visit www.usskiandsnowboard.org